Last month, the only dialysis center in Douma – a besieged town east of the Syrian capital, Damascus – ran out of supplies and was forced to close. Within two weeks, two of its 30 patients had died of kidney failure. They succumbed to a chronic illness, but the Syrian government contributed to their deaths. Last year, the Syrian government repeatedly withheld humanitarian aid from Douma, whose nearly 150,000 residents have been under siege by Syrian government forces since 2013.

As the conflict in Syria drags into its seventh year, the suffering of civilians grows only more immense. The latest round of peace talks in Geneva yielded little progress, and the United Nations Security Council – the body meant to ensure international peace and security – remains paralyzed. Meanwhile, bombings continue on a daily basis and nearly four million people remain trapped without basic life-sustaining supplies in Syria’s besieged and hard-to-reach areas.

Food and infant formula, pain relievers, malnutrition treatment kits, antibiotics, IV fluids, and even antibacterial soap are in dangerously short supply or nonexistent in cities and towns across Syria. These very supplies are stockpiled in UN warehouses in Damascus and Aleppo – in some cases only a short drive from besieged communities – but Syrian authorities will not allow their delivery. In fact, throughout the conflict, Syrian authorities have systematically blocked or stripped vital food and medical supplies from UN aid convoys in order to ensure the prolonged suffering of civilians.

The Syrian government’s routine denial of aid and the resulting civilian deaths are nothing new. Such slow-motion deprivation is a well-established weapon in the government’s arsenal. Last year, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and the Syrian American Medical Society reported on dozens of deaths from malnutrition and starvation in the besieged town of Madaya. Afterward, under international pressure, Syria’s government agreed to a more streamlined aid delivery process that they and the UN said would increase aid deliveries.

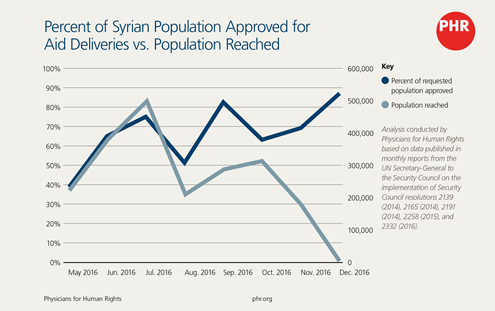

But, as we show in a new PHR report released this week, that aid delivery process has failed to guarantee help for civilians in need. Instead, it has provided a smokescreen for Syrian officials to deceive the world. The new process gives the government the ability to maintain the farce of approving deliveries and appearing cooperative, when, in reality, Syrian authorities later block approved deliveries or only allow insufficient amounts of aid to be delivered. By last December, just 6,000 Syrians received aid under the new delivery process – less than one percent of the population the UN was given permission to reach.

“We now end up in this complete, hopeless bureaucratic quagmire of having to seek facilitation letters, permits, security permits,” Jan Egeland, the UN’s special advisor on Syria said in January. “The way it is now, it cannot continue.”

Yet it continues. The result is suffering and death. And, cruelly, the women and men positioned to help, to treat the many people exposed to this immense degradation – the doctors, nurses, medics, pediatricians, dentists, and pharmacists – have targets on their backs. Since 2011, 782 medical workers have been killed, more than 90 percent by Syrian government forces and their Russian allies. They have been tortured, kidnapped, shot, and shelled. Many have fled while others have stayed behind, placing the lives of their patients ahead of their own.

“The obstacles were everywhere,” Dr. Rami Kalazi, a neurosurgeon who worked in eastern Aleppo city until last summer. “Massive bombardment everywhere, direct targeting of health facilities, a huge shortage of medical equipment and supplies, especially modern diagnostic devices, a demand for ambulances, a huge lack of medicines, a huge gap in medical experts, very few well-equipped ICUs, few beds in ICUs and wards – besides the enormous number of casualties. Could you imagine the circumstances that physicians in Syria are working under?”

It’s impossible to imagine. And there are few answers beyond an insistence that all parties to the conflict in Syria end the sieges and halt attacks on hospitals and medical personnel. But the UN must also assert the authority granted under both international law and Security Council resolutions. It’s time to stop asking for permission to deliver aid. The UN’s humanitarian affairs arm should notify Syrian authorities of deliveries but not wait for approval, as it already does with cross-border aid deliveries.

Each time the Syrian government obfuscates, throws up hurdles, or strips aid from convoys, the UN must document these incidents and report them publicly in real time. The UN must speak out, unequivocally, against the Syrian government’s war crime of depriving civilians of food and medical care. In the meantime, those providing care must be protected.

“My duty as a physician and to humanity is to help prevent crimes against civilians,” said Dr. Mohammed, a surgeon from Aleppo who prefers not to use his real name. “If the world fails to protect doctors and civilians, such silence will affect the entire world. And such crimes will be repeated elsewhere.”